|

Infill Development

Neighbourhood Planning and Design

Neighbourhood Parks

Regional Recreation Facilities

Retirement Accommodation

Rural and Regional Development

Schools

Shopping Precincts

Urban Squares

Workplaces

Case Studies

Making it Happen

Frequently Asked Questions

Getting the Message Out

Image Gallery

|

Development TypesUrban Squares - Full Text |

||||||||

Definition

Urban squares (also called civic spaces, town squares, piazzas or plazas, amongst other names) are spaces that form focal points in the public space network, providing a forum for exchange, both social and economic, and a focus for civic pride and community expression. Their significance and intensity of meaning is typically expressed through “harder” intensively used landscaping. They tend to be formal and urban in nature in contrast to parks and open space, which are typically soft landscaped, larger and less intensively used. Urban squares are typically held in public ownership and designed to be easily accessible by all. |

Forrest Place, Perth |

Urban squares if designed well are thriving spaces that invite people to linger and, interact and connect. They support the popularity of activity centres providing a space for a wide range of formal and informal activities that supports social and cultural life for users of the centre.

Overview

Urban squares attract people because they are active, vibrant, safe and exciting places. Around the world these space have certain common characteristics despite differences in local socio-economic and geographic settings.

The success of an urban square depends on the ability of people to get to the square, to populate it and once there, the ability of the square and its surroundings to support a wide range of users and uses in a safe and comfortable environment. Successful urban squares are designed for people to walk in, stand in, sit in, dance in and to perform in and to look at other people participating in these activities. Successful urban squares convert short in-and-out trips to the centre into a longer and more rewarding social experiences.

Well-designed urban squares encourage people

to congregate and linger

Source: TPG Town Planning and Urban Design

The physical conditions of urban squares have consequences as to how easy and physically comfortable it is to use these spaces. It is presence of people in the space and in the buildings surrounding them that then makes for a safe welcoming environment.

‘Civic spaces are an extension of the community. When they work well, they serve as a stage for our public lives. If they function in their true civic role, they can be the settings where celebrations are held, where exchanges both social and economic take place, where friends run into each other, and where cultures mix. They are the “front porches” of our public institutions – post offices, courthouses, federal office buildings – where we can interact with each other and with government.’ – Project for Public Spaces, 2009

Why?

Well designed urban squares have a number of benefits to the users as well as the urban setting in which they are located. These range from personal and community health to encouraging economic investment.

The great cities of the world are renowned for their grand urban squares which are tourist attractions in their own right. For example Trafalgar Square in London and Piazza San Marco in Venice. However, it is the smaller vibrant urban squares that complement these and are a focus for the local community that are the foundation for the life of the central city and activity centres.

Economic outcomes are a real and likely benefit of investment into improving the public realm. Revitalisation projects that focus on placemaking outcomes result in increased land values and further private investment, which stimulates jobs and supports the growth of local facilities within easy access of the community (Australian Local Government Association, 1997). They also can play a critical role in reversing stigma and providing a highly visible vote of confidence in a community, a view recognised in the successful revitalisation of cities as diverse as Belfast (Northern Ireland) and Tirana (Albania). A view reflected In the European context in the Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European cities (EU ministers, May 2007), which stated “creating and ensuring high quality spaces [is] to be of crucial importance for strengthening the competitiveness of European cities”.

Spaces that offer cultural and social activities will result in enhanced social interaction and community development and will foster increased levels of activity within urban squares. Spaces will be more likely to be used if other people are also using that space. Activities such as people meeting, having conversations and passive contacts (observing or listening to other people), will encourage others to linger. These activities can occur spontaneously as people move about within the same space.

Social activities produce the strongest levels of ownership of the space and correspondingly maximum concern with ensuring other people in the space are safe. Social inclusion can also contribute to an improved sense of community and hence improved mental health (McLeod et al., 2004).

In divided communities which are characterised by one community appropriating space from the other (Belfast, Mitrovice in Kosovo), such squares represent neutral territory and the random interactions it provides can also offer a forum for communication and reconciliation between different communities (United Nations Habitat, 2008).

Increased usage occurs as a result of spaces that are designed to be overlooked with both day and night time activities. Further, the detailed design of a space will contribute to optimising usage, for example, through careful detailed design of such things as where the seating is located, the type of lighting and landscaping, both formal and informal, the richness and texture of the materials used.

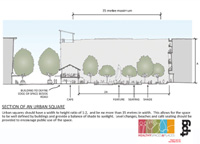

The size of an urban square and whether it is broken down into discrete sub-areas can encourage or discourage degrees of ‘comfort’ and feelings of safety. If the space is too large people tend to linger along the edges and do not interact with other users as much (Gehl, 1987).

Source: TPG Town Planning and Urban Design

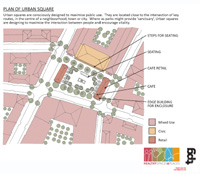

| Rule of Thumb Generally, the optimum size equates to people being able to recognise the other people in the space from one side to the other. On average this equates to a dimension of between 30-35 metres (Gehl, 1987). This is particularly the case where the intensive use of a square is a goal, however where the primary purpose of a square is to frame views of a particular landmark or building, wider spaces may be appropriate. |

Click image for larger version

Source: TPG Town Planning and Urban Design

Streets running past an urban square can enhance access and surveillance. There should be a transition from the space to the street, which may be a kiosk or pavilion or other defining feature. The edging streets should be designed so users are aware they are passing along or through a special space and not just a continuation of the road. Such roads should be designed to minimise their impact as psychological barriers by minimising traffic speed, encouraging a sense of safety and visual predominance to ensure that they do not sever the space from its surroundings.

Buildings around the space can comfortably be up to 5 storeys without overwhelming the space. A building height to width ratio of 1:2 is very comfortable and produces a good urban space. Taller buildings should be set back from the space. Conversely, if buildings are not tall enough to produce an urbanised space other vertical features should be used to increase the sense of enclosure and urban intensity.

In a tight or environmentally harsh urban setting, urban squares can provide a sense of physical and environmental relief to the built environment. They can represent a welcome opportunity to rest, relax or just enjoy a distraction from the intensity of urban life, such as is provided by street art in all its forms. The ‘greening’ of spaces affects the local climatic conditions by shading and providing an evaporative cooling affect (Luley, 2004).

Seating should optimise the view of the space and should not back directly to roads, passing users or doorways. Level changes, planting beds and steps provide a good source of informal seating which will not appear vacant when not in use (Gehl, 1987). Steps should be wide enough to allow for seating without blocking movement and care should be taken to ensure these do not create an obstacle or danger to disabled users.

Urban squares that are well maintained, well used and the centre of community life will encourage respect for the space and foster a sense of pride in the physical as well as social aspects of that space (Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, 2002).

Click image for larger version

Source: TPG Town Planning and Urban Design

Design suggestions for urban spaces

- Strategically locating civic squares at active transport nodes in activity centres will help ensure the space enjoys a “critical mass” of activity.

- Urban squares that are well defined and so far as possible enclosed by buildings will create a strong sense of definition of the space and provide interest. This can be encouraged by a building height to space width ratio between 1:2 and a maximum of 1.5:2. Part of the urban square may have higher buildings or buildings set back from the space.

- Where intensive use is the goal, civic spaces should be no more than 35 metres wide to avoid “agrophobic” areas in the centre of the square.

- A strong sense of connection between the urban square and the ground floor of surrounding buildings can be created through verandahs, bi-folding doors, windows and direct doorways.

- Informal activities or small retail offerings that attract people to linger longer in a space, such as newspaper kiosks or coffee stands, can encourage visits by more people for longer periods.

- Active (day and night time) uses are located around or adjacent to urban square to maximise usage.

- Elements such as quality formal (benches) and informal seating (steps) and lighting incorporated into the design can contribute to the squares identity and character.

- Trees can contribute greatly to the attraction and character of a space by providing shade and good access to winter sun where winters are cool. Subject to careful species selection they can also offer seasonal variety and, allow people to hear birdsong etc.

- Public art works and points of discussion will attract others to visit the space and provide a memorable icon for the space.

- A range of event based activities to occur within the space will foster social capital and increase levels of activity.

Freyburg Place, Auckland

Source: TPG Town Planning and Urban Design

| Rule of thumb Locate urban squares at the nodes of active transport routes and surround them with uses that front onto and activate the space. Once this is done turn the space into an outdoor lounge room with seating, shade, activity and interest. Keep the space public and inclusive and encourage a wide range of activity day and evening. |

Avoid

- Spaces located where they are hard to access from the active transport routes or on the periphery of the activity centre.

- Spaces that are overwhelmed by, or isolated from their surroundings by vehicle through traffic.

- An excess of urban squares undermining the success of any specific space.

- Making urban squares too wide (over 35 metres) other than where they have a special ceremonial use and are not intended to be active on a daily basis.

- Privatisation of spaces or spaces that ‘close’ down after traditional working hours.

- Clutter and visual barriers intruding into the space, restricting their enjoyment and creating unsafe blind spots.

- Defining by buildings that are too low-rise to enclose the space or too tall to allow winter sun sunlight where winters are cool.

- Seating placed with its back to areas of high use or possible danger.

- Steps that are located where they will be a danger to some users.

REFERENCES

Australian Local Government Association (ALGA), 1997, Designing Competitive Places, Creating better towns, cities and places’.

Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (UK), 2002, Streets of Shame, Summary of findings from ‘Public Attitudes to Architecture and the Built Environment’. London.

Gehl, J. 1987, Life between Buildings, Using Public Space, VanNostrand Reinhold Company, New York.

Luley, Christopher J., Nowak, David J., 2004, Help Clear the Smog with Your Urban Forest: What You and Your Urban Forest Can Do About Ozone. Brochure. Davey Research Group and USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station.

McLeod, J. Pryor, S., & Meade, J. for the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, 2004, “Health in public spaces: Promoting mental health and wellbeing through the Arts and Environment Scheme”.

Project for Public Spaces, 2009, Great Civic Spaces. Essay available on line at www.pps.org. New York.

Placemaking Design Guidelines Turning Spaces into Places

United Nations Habitat, Pristina, Kosovo, 2008.

Last updated on 23rd June, 2009

This project was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing.

This project was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing.